By Lesley Dingle and Daniel Bates

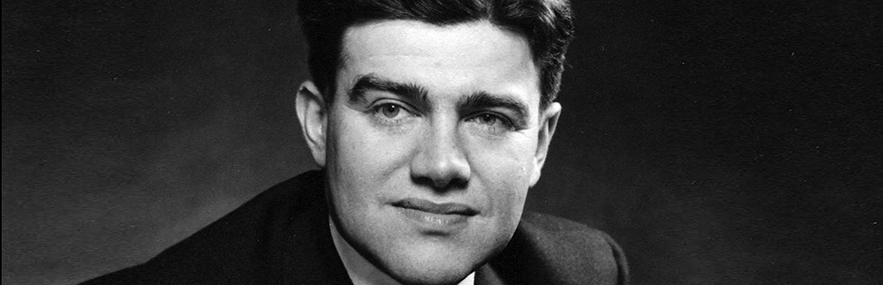

Emeritus Professor Peter Gonville Stein (1926-2016)

- Regius Professor of Civil Law, University of Cambridge 1968-93

- Professor of Jurisprudence, Aberdeen University 1956-68

- Born 29th May 1926

- Liverpool College 1938-44

- Royal Navy, Sub-lieutenant, service in Far East, 1944-47

- Gonville & Caius BA 1947-49

- External LLB Cambridge 1950

- Solicitor 1951

- Borromeo College, University of Pavia 1951-52

- Assistant Lecturer in Law, Nottingham University 1952-53

- Lecturer in Jurisprudence, Aberdeen University 1953-56

- Dean of Faculty of Law, Aberdeen University 1961-64

- Fellow of Queens’ College, 1968-74, Vice President of Queens’ College 1974-81 (Acting President 1976, 1980-81)

- Chairman of Law Faculty Board, University of Cambridge 1973-76

- Visiting university professor: Virginia (1965-66, 78-79), Colorado (1966), Witwatersrand (1970), Louisiana State (1974, 77, 83, 85), Chicago (1985, 88, 90, 92, 95), Padua & Palermo (1991), Tulane, New Orleans (1992, 96, 98), Salerno (1994), Lateran, Rome (1997)

- Hon. QC 1993

- British Academy 1974

- Council of British Academy 1988-90

Additional Material

"Conversations with Professor Peter Gonville Stein: a Contribution to the Squire Law Library Eminent Scholars Archive " (2008) 8 (3) Legal Information Management 214 - 222

I interviewed Professor Stein in the Squire Law Library on three occasions between July and November 2007, and spoke separately to his wife Anne. Professor Stein has been associated with the Faculty of Law at Cambridge University since the before the end of the Second World War, and my abiding impression is of a life-time of scholarship dedicated to liberating an appreciation of Roman Law by the English-speaking world from its Justinian bonds. Other impressions include a finely tuned sense of elegance in both speech and thought, and the priceless gift of being able to bring seemingly arcane concepts and abstruse details into the fresh light of modern formulations.

Peter Stein was born (29th May 1926) and grew up in Liverpool. He entered Liverpool College 1 for his secondary education in 1938. From the outset, a legal career involving Cambridge appeared to have been laid out for him by his father who, although a less than successful barrister, later turned solicitor, had such a sense of loyalty to Gonville and Caius that he had the baby baptised in Caius Chapel and christened Peter Gonville. The pull of Gonville and Caius did ultimately draw Peter, but when he qualified as an Exhibitioner it was to read classics.

As with most children of his generation, the War intruded and his school days were passed at Liverpool College. Despite his school being bombed and a five mile cycle ride each day from his grandmother’s house, his enthusiasm for study was not dimmed, and he excelled in Greek and Latin. Perhaps it was a gift he had inherited from his mother, who was a modern linguist in French and Italian (Girton).

Before he sat the scholarship examinations for Cambridge Peter Stein joined the Navy. Consequently, the few months he spent at Caius in 1944 were as a Naval Cadet. By the time he began his training as a sailor, however, it was obvious that the end of the War in Europe was nigh, and the Navy accepted his application to enrol on a six month training course to become a translator in Japanese. As the accomplished classicist put it, learning Japanese and translating enemy radio messages at his base at Bedford (close to the famous interception centre at Bletchley), was more like doing a crossword puzzle than learning a foreign language.

Despite the somewhat exotic-sounding role he had undertaken, Professor Stein stressed that he was only a translator and that the crash-course he and his fellow service personnel attended did not equip them to function as interpreters. In the end, this was a task taken over by the Americans, who had large numbers of citizens of Japanese descent, so that when he was finally posted to the Far East, it was to the services Education Office in Trincomalee, Ceylon. With little for him to do, the authorities eventually sent Peter Stein to the shore-base HMS Sultan just off Singapore, where he found himself part of the Education and Vocational Training programme. His work entailed handing out leaflets and advice to other servicemen about various trade opportunities that would be available to them in the UK.

Although Professor Stein admitted that it was not very exciting, he found the far east fascinating, which was just as well, as he remained there until 1947, when he was himself demobbed. During this time he was recruited by the British Far Eastern Broadcasting Service as a reader of educational materials. Listeners to the tapes of his interviews with me will agree that his voice has a measured, sonorous quality that suggests that he would have been a natural educational broadcaster.

The delay in Peter Stein’s formal education caused by the War years had two affects on his later career. It provided time to convince him that the classics were not, after all, to be his chosen field, and once he had opted for law, it shortened his legal training.

Stein was twenty one by the time he resumed academic studies in 1947, and his return to Caius was accompanied by a fundamental change in his academic aspirations. He chose the Roman Law option when he tackled Law Qualifying II, and inevitably he fell under the spell of the charismatic Roman Law tutor David Daube. This was probably the most crucial of all his professional relationships. Daube’s is a name that has come up in two of our previous interviews (with Professor Kurt Lipstein and Mr Mickey Dias), and it has always been spoken of with admiration. In those immediate pre- and intra-War years, David Daube gained a reputation for erudition and scholarship that seems to have epitomised so many of the German Jewish émigrés about whom Beatson & Zimmermann compiled their celebratory volume 2.

One amusing anecdote that Peter Stein gave me from this period, emphasised his classics background. On receiving his BA from the hands of the University Chancellor, he commented that he remembers kneeling before him while the Chancellor spoke in Latin, “but with a very strong Dutch accent”. In fact it would have been Afrikaans, because the Chancellor was none other than Field Marshall Jan Christian Smuts.

The other important contact that Stein made while at Gonville & Caius was the result of the circumstances in which the Faculty found itself after the War of having to employ “weekenders” to supplement its teaching complement. These were practitioners who travelled to Cambridge to give a few hours of supervision to the students on Friday evenings or Saturdays, and Peter emphasised to me that the role they played in the Faculty’s history should not be underestimated. One such “weekender”, who taught the Common Law to Peter, was the late Geoffrey Lane, and they kept in touch socially and professionally for many years. It is not difficult to imagine why Geoffrey Lane had an influence because he later became the Lord Chief Justice of England, and gained a reputation for his forthright legal views 3. There is a photograph in the gallery of the two at a Law Society function in about 1980.

The second consequence of the disruption caused by war, was that Stein, along with so many other mature university students in the late 40s, was given various concessions to make up for lost time in their professional training. Peter graduated BA in 1949, but then realised that he could do an external LLB. He took advantage of the arrangement using lecture notes borrowed from friends (graduated 1950), while starting his articles with his father’s legal firm in south-east London the same year, and emerged as a qualified solicitor in 1951.

During the years 1951 to 1953 Peter Stein pondered his career options, one of which took him to high scholastic achievement. In the first year, rather than become a solicitor, he took a scholarship studying Roman Law and learning Italian at Borromeo College in the University of Pavia. The second year at the University of Nottingham as Assistant Lecturer, gave him his first taste of formal teaching, while in 1953 he re-formed his partnership with David Daube. By then, Daube was Professor of Jurisprudence at the University of Aberdeen, and Peter’s move to the “Granite City” initiated his interest in Scots law and the relationship between it and Roman Law.

One of the main pillars on which Peter Stein’s reputation rests, was his realisation that Roman Law, as conventionally taught, at least in the English speaking world (and Italy, apparently), was considered, somehow, to have stopped developing with the production of Justinian’s Corpus iuris (Digest, Institutes and revised Code) in 533AD. Stein’s thesis is that to understand their own legal regimes, students need to study the influence of Roman law on them as they matured over the centuries. It was during his early years at Aberdeen, while still under the influence of Daube, that such notions impressed themselves on him, and led him to write what he considered his most original work (Regulae Iuris: From Juristic Rules to Legal Maxims4). In this he traced the evolution of the rules that underpinned Roman law through mediaeval and renaissance civil law into modern European jurisdictions. It was a theme he developed in a series of books over the years5, culminating, in his retirement, in what he admitted was his best seller “the only one I’ve made any money out of!”, currently (2007) in its tenth printing. This is his beautifully crafted Roman Law in European History 6, wherein he presented the conclusions he had developed during his years of teaching LLB classes on the legacy Rome has passed on to modern European legal codes. He finishes this survey with a comment that “..the institutions of European Community law are frequently described as forming the beginning of a new ius commune”. He concludes however (p. 130) that whereas the mediaeval ius commune was adopted voluntarily because of its innate superiority, this new ius commune is imposed from above in the interests of uniformity.

Stein did not restrict his considerations of the influence of Roman law to Western Europe, and in 1966, during one of his visits to the University of Virginia, explored the degree of penetration it achieved (through the Civil Law) in immediate post-revolutionary America. Although the federal system, with its plethora of jurisdictions and lack of specialisation in the legal profession, seemed ripe for rationalisation in the 1820s, only twenty years later Stein detected that the opportunity had passed, and the study of Roman law had, as he put it "become a part of gentlemanly learning" motivated more by "elegance" than "utility". 7

David Daube’s influence affected Peter in other ways. When the past Regius Professor at Oxford de Zulueta 8 learned that Daube (whom he greatly admired) had to contend with an inadequate Roman Law library, he sold his personal collection to Aberdeen University at a knockdown price. Peter, of course, greatly benefited from these books when he inherited the chair of Jurisprudence at Aberdeen on Daube’s moving to Oxford to fill the Regius chair of Civil Law made vacant by the death of Herbert Jolowicz in 1956. It was a collection the Aberdeen authorities were only too pleased to enhance at Professor Stein’s requests.

In the meantime (1955), de Zulueta had contacted Peter to clarify points from his erstwhile library in connection with a mediaeval document that he was researching. Years later, with the deaths of both de Zulueta, and the original discoverer of the document, Miss Rathbone, Peter was to become deeply involved in this project. It was his introduction into the twelfth century world of Vacarius9 and the teaching of Roman and Canon law in mediaeval England10.

A further advantage that the young lecturer gained from his association with Daube derived from the latter’s extensive contacts amongst continental civil lawyers, many of whom he invited to visit Aberdeen. One in particular, who became a close and influential associate, was Professor Helmut Coing, the legal historian and philosopher who founded the Max Planck Institute for European History11. Stein was invited to serve on the institute’s council, and through his friendship with Coing was strongly influenced in his appreciation of the influence of Roman Law during the Middle Ages in Europe. In particular, he was able to gain access to historical works relevant to what became one of his major interests - Scots law, the Scottish Enlightenment and the importance of the works and teaching of Adam Smith (1723-1790), whom I suspect is one of Peter’s historical heroes12.

Finally, in 1968, two years before Daube moved to the University of California at Berkeley, together with Professor Patrick Duff (the retiring incumbent), he recommended Peter’s name to the Patronage Secretary of Prime Minister Harold Wilson for appointment to the Regius chair of Civil Law at Cambridge.

It is difficult to not appear presumptuous when commenting on the output of a scholar whose writing is a joy to read, but the number of reviewers who also have referred to Peter Stein’s works as “elegant”, “lucid”, “concise” and full of “light touches” allows me to add my admiration for his style and clarity without being patronising. When I asked him if he thought it was a technique that he had improved with time, his modest reply was “I hope so. I tried to be clear. I once said in a lecture that it is more important to be clear than to be right”.

A further trait that I might add from my own short acquaintance with Professor Stein is his enthusiasm and love for his subject - it was obvious that he delighted in exploring avenues in pre-nineteenth century legal and historical writings. Each of these journeys resulted in a solid core of legal relevance together with delightful anecdotes and exquisitely researched historical esoterism.

This side of Peter Stein’s work is crystallised in the essays he chose for a compendium which was published in 1988. My favourite is the one about Sir Thomas Smith, who, like the writer, was Regius Professor of Civil Law at Cambridge (1540, inaugural appointment by Henry VIII) and a Fellow of Queens’. Stein dedicated this essay, on the intricate balance between civil law and theory of the state, to his friend Professor Ben Beinart who, at the time (1977) was at Birmingham University. Through Stein’s pen, Sir Thomas comes alive and the essay is littered with unforgettable anecdotes: who can not pause and admire the single-mindedness of a man who, languishing in the Tower of London not knowing his fate, chose to pass his time translating the Psalms of David into metrical English verse.

Although Peter Stein was Regius Professor for twenty five years, and had been at Caius for a further three, I gathered few reminiscences and anecdotes about his colleagues13. This is because he was not inclined to pass judgment but he recounted one amusing story I can place before readers, because it poses a legal conundrum. It revolves around H. Barnes14 who lectured in criminal law when Peter was an undergraduate. Apparently, students would flock to one particular lecture for which Barnes became famous and in which he discussed an appeal case dealing with the feasibility of committing buggery with a duck. The finale was a theatrically delivered verdict, in an Irish accent, of “conviction quashed”. Thereupon Barnes dramatically turned the page in his notes and the lecture room rapidly emptied.

Despite what must have been a propensity for time-consuming research (whatever his protestations that “...Roman law doesn’t change all that rapidly...”), Peter Stein was always prepared to share his talents with the wider community. These extra-mural activities varied from professionally- related membership of important national and international committees such as the Council of the Max Planck Institute for European History (1966-88), UK University Grants Committee (1971-75), Public Teachers of Law Society (he served as President in 1980-81), Council Member of the British Academy (1988-90), the US/UK Fulbright Committee (1985-91) and Vice-President of Queens’ College (1974-81), to pastoral activities in his local community.

When I asked him about the latter, he replied modestly “Well, I always felt I ought to do a little bit in the community...” At Aberdeen, this took the form of his involvement with the financial and administrative problems experienced by mental hospitals, and he said his interest arose from concern with what he called their “Cinderella” status within the hospital system. For five years he served on the Board of Management for the Royal Cornhill and Associated (Mental) Hospitals, and for three he was a member of the Secretary for State for Scotland’s Working Party on Hospital Endowments, where he fought the corner for mental hospitals. Listening to his account, I found it greatly poignant that a man so obviously liberated by his own mental powers should have been moved by the plight of “...very old people who had been dumped there [in mental hospitals] because there was nowhere else to put them”.

When he moved back to Cambridge, Professor Stein followed in the footsteps of the then past President of Queens’, Dr Arthur Armitage15, and despite the long hours it required, he served in the city of Cambridge as a local magistrate (lay justice of the peace). Traditionally, the Law Faculty obliged with one or two members for the bench, and Peter served with his friend and colleague John Hall16. Sitting in threes, and deciding by majority, he said that determining the guilt or innocence of local law-breakers was usually straightforward, but it was with deciding on appropriate sentences that he had most difficulty. Peter claims that he tended to err on the side of leniency, but that some of his colleagues were more severe. I might add, however, that his wife Anne told me that there were occasions when her husband was quite adamant in insisting on punishing offenders, since everyone should be treated equally! She recounted, with some amusement, how once he fined a nun for parking her moped outside a church.

As with my other interviewees, I came away from my meetings with Professor Stein with a great admiration for his scholastic integrity and a sense of his humbleness before a subject to which he is still dedicated. I also became aware of the sense of obligation to his subject and the Faculty during his tenure of the Regius chair. Anne told me that having resuscitated interest in teaching and research in Roman Law at Cambridge, he refused the temptation of lucrative offers to move to America, because he feared that the subject would lapse again.

Finally, although not in the best of health, I am grateful for the good-natured way Professor Stein persisted in his collaboration with the project, and how he responded to my queries and requests with candour, wit and humour. I must also add a particular word of thanks to Anne Stein, a solicitor in her own right, for her participation in this tribute by way of her delightful anecdotes, and for the wonderful photographic record of Professor Stein’s career that she has provided for the website.

Lesley Dingle - Acquisition and Creation of Content

Daniel Bates - Visual Presentation, Technical Enhancement and Audio Editing

- 1 School website. Both Latin and Classical Civilisations are still taught as subjects. The school is now co-ed. http://www.liverpoolcollege.org.uk/departments.shtml

- 2 Beatson, J. & Zimmermann, R. (eds). 2004. Jurists Uprooted, Oxford University Press, 850pp.

- 3 Geoffrey Lane (1918-2005), Lord Chief Justice (1980-1992). Was part of the prosecution team during the trial of the Great Train robbers (1962). Stirred up great controversy for his role in the appeals process of the Birmingham Six (1987) and Guildford Four (1989) cases during the IRA bombing campaigns. See:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoffrey_Lane,_Baron_Lane - 4 1966, Edinburgh University Press, 206pp.

- 5 For example: Legal Values (1974, with J. Shand), Legal Evolution (1980) and Legal Institutions (1984)

- 6 1999, Cambridge University Press. It is in fact a translation of Römisches Recht und Europa, Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag 1996.

- 7 "The attraction of the Civil law in post-Revolutionary America" Virginia Law Review, 52 (1966), 403-34.

- 8 Regius Professor of Civil Law 1919-1948

- 9 1120-1200?, first teacher of Roman Law in England (Oxford 1149), educated in Bologna, brought to Canterbury, possibly by Thomas Beckett in 1143.

- 10 Professor Stein eventually published a book to which he attributed posthumous co-authorship to de Zulueta: de Zulueta & Stein, 1990, The Teaching of Roman Law in England around 1200.

- 11 1912-2000. The institute was founded in 1964 with Coing as its Director. He retired in 1980. Coing was from an originally French Hugenot family that settled in Hannover.

- 12 Professor Stein published on a set of Adam Smith’s lecture notes that were “discovered” in 1958. Meek, Raphael & Stein, 1978, Adam Smith: Lectures on Jurisprudence. OUP. He also gave the annual lecture to The Stair Society in 1977 entitled “Adam Smith on Law and Society”.

- 13 I estimated that he would have had ~19 professorial and 58 non-professorial colleagues over the period 1968-93, as well as meeting 20 visiting Goodhart professors.

- 14 Fellow of Jesus College, Lecturer in Law 1932-1959.

- 15 Lecturer in Law 1950-70

- 16 Fellow of St Johns and Lecturer in Law 1961-85

Twitter

Twitter

Instagram

Instagram Facebook

Facebook YouTube

YouTube