By Lesley Dingle and Daniel Bates

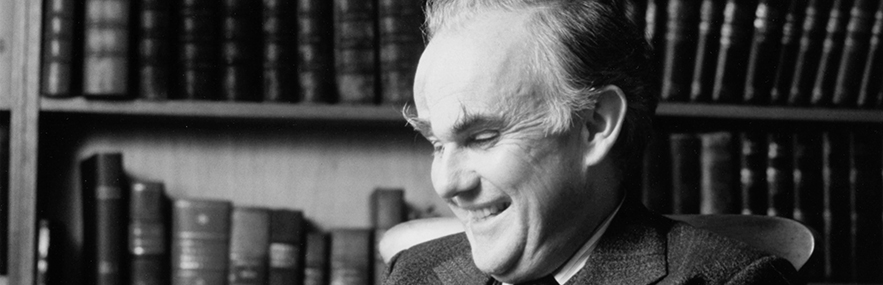

Professor Stroud Francis Charles (Toby) Milsom (1923-2016)

- 1923: Born, 2 May in Merton, Surrey

- 1941-44: Trinity College

- 1944-45: Naval Intelligence

- 1947: Called to Bar, Lincoln’s Inn

- 1947-48: University Pennsylvania, Commonwealth (Harkness) Fund Fellow

- 1948-49: Yorke Prize and Fellow Cambridge Trinity College.

- 1949-55: Fellow & university lecturer Trinity College

- 1955-56: Lecturer, London School of Economics

- 1956-64: Fellow, Tutor & CUF lecturer (‘56-64), Dean (‘59-64) New College Oxford

- 1964-76: Professor of Legal History, London School of Economics

- 1976-90: Professor of Law, Cambridge

- 1990: Retired

Additional details

- 1958- 70: Visiting Lecturer New York University Law School

- 1964-80: Literary Director, Selden Society

- 1967: Fellow British Academy

- 1968-86: Visiting Professor Yale Law School

- 1970: Hon. Bencher, Lincoln’s Inn

- 1970- Fellow, Roy Historical Soc

- 1971- Corresponding Fellow, American Soc for Legal History

- 1973: Visiting Professor Harvard Law School & Dept History

- 1975-98: Member Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts

- 1976: Exchange Visitor to Japan

- 1976: Fellow of St John’s College

- 1977: Charles Inglis Professor Colorado University Law School, Boulder

- 1981: Visiting Professor, Monash Uni

- 1985: QC

- 1985-88: President, Selden Society

Lectures and awards

- 1972: Maitland Memorial Lecturer, Cambridge

- 1974: Addison Harris Memorial Lecturer, Indiana Uni Law School, Bloomington

- 1980: British Academy Lecture (On a Mastermind)

- 1980: Selden Society & Pembroke College Oxford, Blackstone Lecture

- 1981: 10th Wilfred Fullagar Memorial Lecture, Monash

- 1986: Ford’s Lecture in English History, Oxford

- 1995: Carpentier Lecturer Columbia Uni

- 2001: Westminster Abbey - F. W. Maitland memorial unveiling

- 1972: Ames Prize, Harvard

- 1974: Swiney Prize for Jurisprudence, Royal Society Arts

- 1981: Hon LLD Glasgow

- 1984: Foreign Member American Philosophical Soc

- 1985: Hon LLD Chicago

- 2003: Hon LLD Cambridge

Additional Material

"Conversations with Emeritus Professor Stroud Francis Charles (Toby) Milsom: A Journey from Heretic to Giant in English Legal History" (2012) 11 (4) Legal Information Management 307 - 316 (SSRN citation)

The academic achievements of Professor Toby Milsom have led the current (2010) Chairman of the Faculty of Law at Cambridge University, Professor Ibbetson, to describe him as the “dominant intellectual voice in English Legal historiography” for the last fifty years1. This position, I am sure Professor Milsom would be the first to acknowledge, has been born out of an intellectual struggle with what he himself calls a “superhuman myth”2 - the legacy of Frederic William Maitland. When he gave a eulogy on unveiling a memorial tablet in the South Transept of Westminster Abbey on January 4th 2001, ninety-five years after Maitland’s death, Professor Milsom described this “extraordinary man”, who had laid “..the foundation of all that we know about the history of the common law...3”, as someone with whom he was destined to “..argue[d] for much of my life...4”.

Given the inevitable clash of notions that were thrown up during the course of this career-long crusade, Professor Milsom continually had to defend his self-styled heresies (what he also called “an anti-creed of disbeliefs”5) against the Maitlandian tradition, and it is a tribute to his own brilliance that Professor Ibbetson was able to proclaim in the latter years of this struggle that some, at least, have now “crossed the line into orthodoxy6”.

It is also perhaps fitting that two such doughty champions of legal historiography came at their subject, in the same forum, from similar perspectives: namely a sense of disappointment in their initial brushes with academia at Trinity College Cambridge. In his case, Maitland was thwarted through a weakness in mathematics (and only succeeded through the sponsorship of Henry Sidgwick7, who converted him to the study of moral philosophy) while on his arrival Toby Milsom was abruptly diverted from his chosen course by a similar failing in his wish to study science. Certainly, in his case, he “never quite suppress[ed] a hankering for test tubes8” and one does not have to look far below the surface of Professor Milsom’s writings to expose his continuing allusions to the natural and physical sciences. It is a fascinating source for allegory, and several commentators on his works have taken up this theme, as he did himself when commenting on Maitland’s Darwinian perceptions9. More of this anon, as it clearly influenced his view of his chosen, third subject.

But for such vagaries, our understanding of the common law might well still be deficient in the areas on which Professor Toby Milsom deemed to shine his talents.

Toby was christened Stroud Francis Charles in 1923, and it fell to his elder, late brother Darrell10 unofficially to christen him yet again in “resemblance to a Toby jug”. He was born in Merton, Surrey, whence the family soon moved to Wimbledon from where his father11 had a complicated daily railway commute via Clapham Junction to Whitechapel. Here he was employed as the Secretary of the London Hospital12, then “the biggest voluntary hospital in England, possibly the world”. Wimbledon, however, was an ideal base for Toby’s mother who used the family car to attend her golfing appointments: she had been the New Zealand ladies champion at the age of fourteen and was “a very good golfer”. For Toby and his brother it was also convenient for them to attend the class for little boys offered at the Wimbledon High School for Girls - “a very grand establishment,” before later being despatched to a prep school in Guildford, and later still for their high school education at Charterhouse in nearby Godalming. Toby Milsom’s upbringing in the years before the Second World War was, therefore, comfortable and well ordered.

In the event, Charterhouse was not to his liking, and he “hated it”, so much so, that on the one occasion that he did return in later life he and his wife “drove around the school grounds because I thought she ought to see it, but we didn’t get out”. His time there did leave him with one lasting legacy, however - his love of science. Consequently, he became “what they grandly called a Science Specialist”, and for his final Higher School Certificate examinations he took physics and chemistry. His heart was set on a career in these subjects, but it was not to be. The outbreak of the Second World War, combined with a recent traumatic event, contrived to shift irrevocably his life and career in an entirely unforeseen direction. Legal history and our understanding of the development of the common law were the beneficiaries, but despite the acclaim he eventually achieved in these new ventures, it was not a decision he ever outlived. The depth of his schoolboy commitment was revealed in the last book Professor Milsom published, where he was moved to describe himself as “one who had turned reluctantly from natural sciences to the law and who could never quite suppress a hankering for test tubes”13.

The event that began to shape his ultimate course had its origins in Toby’s father acquiring a cottage in Cornwall where the family spent much of its time during the 1930s (they eventually moved there permanently when the house in Wimbledon was damaged during the War). It was here, while he was on holiday from Charterhouse in early 1938, that Toby suffered a serious wound to his head and was taken to Plymouth hospital, where the prognosis for his recovery was not good. Luckily his father was able to persuade the foremost neurosurgeon of the day, Hugh William Bell Cairns14, who was currently attending Unity Mitford (Adolf Hitler’s admirer, who had attempted suicide at the outbreak of war) to journey to Plymouth to look at Toby’s wound. A special ambulance train was laid on, and the seriously ill boy taken back to the London Hospital, and later to the Radcliffe, where Cairns eventually “opened me up and mended it [his cerebral wound] with a sort of puncture kit”. After a year of recuperation, Toby made a remarkable recovery: most of Cairns’s patients “survived the operation [but] hardly any survived much longer”, and he returned to Charterhouse to complete his schooling.

With his exams completed, but war underway, Toby received his call-up papers, and at this point the benefit, if that is the right word, of his mishap came to the fore. Instead of being drafted into the war (his brother had by this time died in action in the RAF), Toby was told to “go up to Cambridge and just pretend life was normal....the military people interviewing me said “go and make yourself into a real person because there aren’t going to be many of them around”“. Thus spared, Toby packed his trunk of books on physics and chemistry and in 1941 presented himself at his father’s alma mater, Trinity College Cambridge where he planned to tackle the Natural Science Tripos.

At this point, fate took a further hand, when his tutor at Trinity informed him that “you’re okay at physics and chemistry, but your mathematics is hopeless. It’s no good trying to be a scientist in the 20th Century without being a good mathematician, so you’d better do something else. What will you do?” At this news, Toby was “very, very upset”, and reluctantly plumped for “English”. His tutor poured further cold water on this suggestion with “Want to be a school master?”, and he finally settled on his third choice “Law”, to which his tutor said “done!”

In retrospect, Professor Milsom’s views on law accord better with his original aspirations than his initial reaction might have suggested - “the law had one great advantage over, for example, History or English...in that one thing follows from another - or more or less” and to a scholar who had been so thwarted “that was comforting to one who would like to have been a scientist”. Although his ultimate verdict on the path he had been forced to follow was that “I enjoyed it”, it is a sobering thought that only through these contingencies was the “dominant intellectual voice in English Legal historiography” of the latter 20th Century eased onto his collision course with the then conventional wisdom on mediaeval English law as had been enunciated by Frederic William Maitland half a century earlier.

Toby Milsom was an undergraduate at Trinity College from 1941 to 1944, and by his own account it was a “life of luxury” (presumably in comparison with life in the rest of war-time Britain), but the college was a “very strange place”: there were no young dons, and very few fellow students - everyone else was at the War. His reminiscences on this unusual period were fascinating, and it is worth highlighting a few aspects.

In this abnormal environment Toby fell under the influence of some of the strong and charismatic legal scholars still inhabiting the Faculty. Foremost was “dear old Buckland” who taught him Roman Law15. He had been the Regius Professor of Civil Law since 1914 and was at this stage well into his eighties (he died in 1946). Toby was fascinated by the old doyen’s “mathematical approach” to teaching - “he liked to work things out in front of you”, and with his science background perhaps it was inevitable that Toby would become what he called the “anchor man” in their small group. Professor Milsom admitted, however, that he and his class mates “were horrid” to the “great man”. Buckland had originally been trained as an engineer at the Crystal Palace School of Engineering16 before entering Gonville & Caius in 1881 (where he stayed for the rest of his life), and he had a habit of propping himself up to see over the top of his lectern (he was very short). Inevitably the structure toppled forward as he tired and caused the old man to bounce up and down, to the amusement of his audience. Nevertheless, the years have not dimmed Professor Milsom’s affection for one who inspired him and whom he remembers as being “very kindly.”

He was similarly fond of Percy Winfield17 who was then Rouse Ball Professor in English Law. Over the years Toby came to know the Winfield family particularly well, as Professor Winfield annually rented a grand holiday house close to Toby’s father’s home in Cornwall, and the families socialised. Although Winfield retired from his chair in 1943, while Toby was still an undergraduate, he believes that it was Winfield’s continuing influence at Trinity College that was instrumental a few years later (1949, only four years before his death) in his being offered a Trinity Staff Fellowship. This was clearly a crucial event in Toby’s early career, as it later gave him the shelter he needed from which to establish his credentials in his somewhat esoteric chosen discipline.

The topic to which Toby eventually turned his attention was legal history, and in this regard a further crucial influence was Harry Hollond18, who took the Rouse Ball chair when Winfield retired in 1943. Hollond was a country squire whose mother owned an impressive estate in Suffolk and Toby recounted some amusing anecdotes of visits to this antiquated retreat19.

“He insisted on my wife and me going to visit his mother and sisters in their very grand house near Bury St. Edmunds. It was a grand place. The gardener’s cottage had absolutely everything, all mod cons, but they didn’t. Earth closets. By choice, I mean there was more money than you could shake a stick at. His father had been a merchant in India. I don’t know what in, but had made a fortune. So there was a lot of money, most of which eventually went to Trinity....A really eccentric family. Harry had three sisters, they were all a bit batty and when Iréne and I went to stay his mother insisted on taking me for a walk and after about an hour Iréne began to fidget and say, “Well he’ll exhaust your mother, she’ll be worn out. “You wait”, they said. She came back as spry as anything, carrying armfuls of logs, making me carry armfuls and I was shambling along absolutely exhausted. She didn’t make it to 100, but she nearly did. Extraordinary family. Extraordinary house, beautiful house.”

Hollond himself was a “very intimidating character” and another strong presence at Trinity College, where he occupied an attic apartment in Nevile’s Court (while his wife lived in Girton College, where she was Bursar). It was he who, while Toby’s Director of Studies in his final year, encouraged him to develop his interest in legal history. As a result, Toby ultimately had much to thank Hollond for in this regard, despite being rather dismissive of Hollond’s credentials in this area. Although he called himself a legal historian, Hollond “never wrote anything about it as far as I know”, seemingly a tradition of Trinity legal scholars of that vintage.

Another notable Trinity man was Professor Duff20 who, despite his lack of output (he published one paper and a book) was elevated in 1945 to the Regius Chair in Civil Law, and was one of Toby’s earlier director of studies and a further teacher of Roman Law. Duff was originally a classical scholar, only taking to the law when awarded a “grand scholarship that the Inns give” when excelling at his Bar exams. Professor Milsom described him as a “funny man”: Scout Commissioner for Cambridgeshire, and recalled with amusement the occasion when he and his girlfriend bumped into Duff in a Cypriot restaurant one evening (presumably after the war) resplendent in full Scout regalia, while both parties “pretended not to see each other”!

One larger than life character who taught Toby was Henry Barnes21. Barnes “had been ejected.... he’d been a Fellow of Jesus..... Anyway, he had to set up teaching heaven knows how many hours a week, from rooms in Sidney Street, if I remember rightly.... He lectured on Criminal Law...was an exciting lecturer rather than a useful one... everything about Henry Barnes was exciting. He was rumoured to have been President of Mexico for a few days; it’s more than possible. He was a great figure”.

Two other personalities impressed Toby as an undergraduate: one was the most decent person he ever met (Emlyn Wade22, who became the Downing Professor the year after Toby graduated), and the other the nicest (Hersch Lauterpacht23, then Whewell Professor of International Law). The latter was a “lovely man - very kindly, charming, unselfish, helpful to everybody”, but he was unable to inspire Toby’s interest in international law, which he “detested” partly as a result of hearing Professor Lauterpacht read the beginning of his own draft of the Charter of Human Rights, which he was unable to take seriously as a legal document.

A further staff member whom Professor Milsom remembered with particular fondness from these wartime days was David Daube. Daube was a tutor at Gonville & Caius, and as recalled by Professor Milsom (perhaps apocryphally), he had been rescued from the anti-Jewish sentiments welling up in Germany by Buckland, who in 1932 “hired an aeroplane and flew off to [Göttingen]....and just brought him back....because he wouldn’t have survived long”. Daube (who incidently, was a seminal influence on another of our Eminent Scholars, Professor Peter Stein) taught Roman Law to Toby Milsom, and he recalled fondly how “he was a very sweet man....in wartime not many dons invited their pupils to their houses for drinks or anything else, because supplies were short...but Daube asked me to tea.”

Finally, Professor Milsom mentioned a wartime personality who seems to have eluded the reminiscences of our previous Eminent Scholars: a certain Charlie Ziegler. He was a very hard working teacher who “probably taught every first year law student, and ...worked from dawn to dusk.... 8 in the morning until 8 at night every day of the week except Sunday. He was a lecturer in Pembroke, but was never a Fellow....They gave him rooms and I think he was a college lecturer. He was a wonderful teacher, and it wasn’t just Trinity first years I think who were sent to him, I think the whole University sent their first years to him, so there was certain mechanical nature to some of his tutorials, some of his supervisions. He was deeply deaf and beasts that we were, he had a microphone in the middle of the table and he was an old man and occasionally he’d go off to sleep and we found that tapping the microphone with a pencil worked wonders”. As with David Daube, Charlie Ziegler impressed Toby Milsom with his wartime generosity, inviting the student to his home for a meal. (Ziegler was also remembered as an assiduous and effective lecturer by both the late Sir Michael Kerr24 in his autobiography, and Sir Richard Stone25 in an interview).

The War dragged on, and Toby Milsom, coming to the end of his studies, made efforts to prepare himself to play some role in the conflict. To this end he organised himself a job with Naval Intelligence, and he took this in 1944. He joined a research unit which amassed detailed facts about places the allies hoped to capture or recapture, with the purpose of planning for the peace, as it would now be called. Professor Milsom wryly commented that he thought Donald Rumsfeld26 could have benefited from such work before the Iraq war.

Originally the group occupied quarters in the School of Geography at Oxford University, eventually moving into Nissen huts on Jowett Walk, while the senior Admiralty staff were housed in nearby Manchester College. Toby found the work and the people very interesting, in fact he said that “it was a silly thing to say of a wartime job, but it was actually fun,” to the extent that he felt that “in a way, I was educated on the Balliol Cricket pitch”. Most of his colleagues were relatively senior military personnel under the command of a Major of Marines, and they hailed from several allied countries - Norwegians, Dutch and French. Their work was painstaking in its detail, covering every aspect of the population and facilities of their selected targets. In addition to the satisfaction that the work gave him, Toby benefited from his stint in Oxford in two ways - he became familiar with the university27, and he made the acquaintance of Major Robbie Jennings28. At the time, the chasm between them in rank was “as wide as that between Cambridge colleges”, but Jennings was destined to follow Hersch Lauterpacht into the Whewell Chair at Cambridge (1955-81), and later became President of the International Court of Justice (1991-94). And his exposure to Oxford was to stand him in good stead a few years hence.

Once the War ended, Toby Milsom took only two years to re-orientate and set off in search of the mysteries that Frederic Maitland had unearthed but not, tantalisingly, solved. Initially he returned to Trinity which put him up and was grateful for some income. Here he studied for his bar exams, and had a plan to “use what remained of my scientific background” to follow a career in the Patent Bar, where he thought his interests might be satisfied and he could earn “a fortune”.

Although Toby passed his bar exams and was called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn, his plans for the Patents Bar never came to pass, and in 1947 he was awarded a Commonwealth Fund Fellowship29 (an award analogous to a Rhodes Scholarship, but for British graduates to study in the USA). Toby had settled firmly on legal history as his research area, and as he explained, the awarding committee directed recipients to a venue where they could be supervised by an expert in their selected topic. The obvious candidate was Sam E Thorne 30 of Harvard, but he was, somewhat perversely, in England at the time, so Toby headed for the Law School of Pennsylvania. Here he fell under the wing of George Lee Haskins31, the A. S. Biddle Professor of Law at Penn Law32, and son of the legendary Charles Homer Haskins33, (doyen of US mediaevalists). “George was wonderful....amazing man” and blessed with a photographic memory, so that whenever Toby wanted assistance, Haskins could quote the references as if “flicking through the pages in his mind”. The year at Penn Law was a great success - “I had a lovely time” - and Toby submitted the dissertation that he produced to Trinity College for a Prize Fellowship. To his surprise he was awarded it (he suspected that Harry Hollond was behind it), and it also won the 1948 Faculty of Law Yorke Prize.

After a year at Trinity College, he was taken on as a Staff Fellow (and here he suspected the hand of “old Winfield”), and it could be said that his career was now on a stable foundation. Such was (is) the nature of these things, that now ensconced in a secure college position he was able to contemplate legal history as a long term prospect: “I thought there must be more to it than what emerged from an undergraduate course” and so that while he considered such a decision as “self-indulgence....I didn’t have to worry....it didn’t much matter whether I did something that people wanted or not....nobody wanted legal history and they still don’t!”, these were not issues for which he would be held to account. He could follow his esoteric interests unhindered.

Despite this, life as a lecturer was demanding. With the influx of returning “warriors” from the war, student numbers rapidly rose and Toby found himself teaching mature students already in their thirties - he was himself only twenty-five - many of whom had experienced considerable responsibility. He contrasted his situation with that of his fellow teacher Kurt Lipstein who, at 39 was a little older, and from whom they expected much more. Nevertheless, Professor Milsom said that he had a lecture each day at 9am, and that for this he habitually started preparation at midnight, and delivered it “fresh off the cooker, as it were” - an “horrific” arrangement.

Toby Milsom chose to leave Cambridge in 1955 and was offered a lectureship at the London School of Economics where Hermann Mannheim34, one of the famous uprooted German-speaking jurists35 and the “father”modern English criminology, had established the teaching of criminology in the immediate post-war period36. The LSE had, in fact, been relocated to Cambridge during the war years (1940-45), when it occupied The Hostel in Peterhouse College on Trumpington Road.

Toby’s year at LSE gave him time to re-establish himself, but it was not particularly happy as he and his wife were blighted in their accommodation in Chiswick, and Toby was forced to teach mainly property law and contract. He refused to teach tort. But salvation was at hand, and his time at Oxford during the War paid dividends. He was invited to dine in New College “in the typical Oxford fashion”, and in 1956 was offered a post for which he did not apply and a Fellowship at New College.

Toby stayed at Oxford for eight years (until 1964), and by the time he left had begun to establish a high reputation as a scholar of English mediaeval law. New College was a venue in which he thrived, but his teaching schedule was “the heaviest...I ever had” and he had to pace himself carefully so as “not to let go of whatever I was trying to write in term time - do a tiny bit every day, or at any rate every week, just so as not to slip back to the starting point”. Nevertheless, it was during these years that he laid the solid foundations on which his later formidable reputation was to rest. In 1958 he was approached by Professor Plucknett37 to take over his role in writing the introduction (which amounted to the legal background) to the translations and interpretations of the Novae Narrationes (narratio or counts = opening addresses of cases by plaintiff’s counsel) written in Anglo-Norman dialect which had been started by Dr Elsie Shanks in 193338. As part of this work, Toby used to regularly commute to the Public Record Office in Chancery Lane where he consulted and translated the clerks’ cryptic records in Anglo-Norman of the parchment plea rolls which entailed “two brown coated men stagger[ing] in carrying on a stretcher....a sort of coffin-like object, which [was] the roll for one term, which may have had up to a thousand membranes and weigh[ed] a ton.” These records were the treasure trove that Toby patiently mined for the rest of his career, and upon which he founded his heresies of the Maitlandian tradition.

Toby also immersed himself in college administration and he was appointed as Law Tutor (where he succeeded J. B. Butterworth39), and later Dean. As Dean he was responsible for attending to various “events” occurring around college (including being on tap for queries raised by the night porters) and he recounted a revealing account of the casual, if eccentric, manner in which colleges in those days went about their affairs. The story related to the donation to New College Chapel by Major Alfred Allnatt of a painting by El Greco. Allnatt, a very wealthy businessman and philanthropist phoned the college one day “I live in a flat and I haven’t got room for all my pictures. I’ve got this El Greco I want to get rid of, would you like to have it?” Well, if I’d been the Warden I would have assumed it was a hoax, but he was an experienced man and said “Yes, of course”. The benefactor was driven up by his chauffeur one Saturday afternoon. I went round to help the Warden with the chauffeur carrying the picture, the benefactor carrying the hammer and nail....in the Chapel the benefactor said, “How about there?” and the Warden said “Yes, that would be nice.” So the chauffeur climbed his ladder and banged in a nail and this picture, worth a fortune, was hung. Nothing is easier than to get into a college chapel, so we had a burglar alarm fitted. It was one of those damn things that go off every time a fly passes through its rays. So, I spent a good many restless nights having to go in because the night porter had rung saying, “Sir, alarm.” Nobody ever did steal it and, so far as I know, it’s still on its hook.”

Both Toby and his wife were very attached to their life at Oxford and their beautiful college house, but inevitably, with his growing reputation, academic destiny beckoned him away from New College. In 1964 he was offered the chair of Legal History at the London School of Economics when it was vacated by “old Plucknett”, one of Frederic Maitland’s disciples: “my wife and I were deeply torn...[but] it was something I felt I couldn’t refuse, so we went”. This time, his stay at the LSE was far happier, and there followed the most productive period of his life, with three major text books, including the first edition of his seminal Historical Foundations of the Common Law40 (although most of the work for the latter had been done at Oxford). It was during this period that Professor Milsom developed and elaborated upon his famous “heresies” apropos the fashionable Maitlandian notions regarding the mediaeval evolution of the common law, which he expounded in great detail in a style that some reviewers found (and still find) both nuanced, exciting, intensely thought-provoking, and above all, controversial.

When asked about the circumstances of this intense period of research at the LSE, Professor Milsom was remarkably candid and relaxed. He worked single mindedly - he had a room at LSE that was “very, very hard to find” and was “pretty much left to my own devices”. Also, he organised his lecturing so that he compressed it into a day and a half a week, and “spent the rest of the time at home” - “I never did much legal history in my office...it all went on at home”. And home was a very pretty house “in a row of nice houses [in Greenwich] built by a dishonest 18th century steward of the Earls of Dartmouth” that entailed a “nice commute” by train from Lewisham to Blackfriars.

One reason for spending so much time at home was that “LSE never alters. There’s nearly always a riot in the front hall, with people shouting obscenities at the Governors..”, and although he recounted this with his usual infectious humour, it was clear that he found the overall atmosphere not conducive to his research. Of course, the 70s were a time of student rebelliousness worldwide (fuelled by anti-Vietnam war protests), and Professor Milsom recounted amusingly that even at Harvard, where he taught historians and other courses in the Law School in 1973, trouble brewed: “I was going to my undergraduate course one day [when] a very large student came up and stood over me and said “Mr Milsom, you really oughtn’t to be giving this lecture”. I didn’t have time to think, so I said, “Well, .....ah, but then I’m just an unreconstructed fascist pig.” He was so shocked he stood back and let me pass. Some of my flock were following me at a distance, they didn’t want to get involved in all this, but they were quite impressed.”

Nevertheless, his teaching was an important component of his modus operandi because “I’ve always thought that there’s nothing like lecturing for making one sort out one’s own thoughts”, and in Professor Milsom’s case, his thoughts stirred up much comment. Many of the reviewers to the First (and Second, 1981) editions of his major work, Historical Foundations (by his own acknowledgement his most important work, written while at LSE) emphasised that whatever its strengths, it was not a work for beginners, or those unversed in legal history. This was despite the fact that “Butterworths commissioned it as a student book....but I was just writing it for myself, I’m afraid.” Professor Milsom clearly had not changed his uncompromising approach to his work in the nearly twenty years that had elapsed since his Fellowship at Trinity.

Now established as a foremost thinker and contributor to English legal history, Professor Milsom was elected a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society (1970), and a member of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts (1975). While the former he dismissed as merely “kindness on their part”, “I never went to a meeting of the Royal Historical Society”, the latter turned out to be “quite interesting....quite fun”, and he was active in it for thirteen years. It was a Government organisation that attempted to facilitate scholars’ access to historical documents in the possession of wealthy owners, one of whom was the then 12th Duke of Northumberland, who came to every meeting in his Rolls Royce from his palatial residence (Syon House) in Chiswick. Meetings were held in the Commission’s office just off Chancery Lane in Quality Court, and the body played a useful role in bringing scholars together with owners who “weren’t always too willing because only the very richest had a permanent librarian and they weren’t any too keen on letting their treasures just go walkabout...”. Needless to say the Commission ceased to exist “in some Whitehall economy move...and it is now part of the National Archive” in Kew, and “I had to resign when they moved” (in 1998).

In 1976, after twelve years at LSE, Professor Milsom came back to his spiritual home, although by now the Trinity College trio of Professors who had been so influential in his earlier years had either died (Hollond, 1974 and Winfield, 1953) or long retired (Wade, 1962). The chair of law was advertised, but Professor Milsom did not apply for it. However “they actually approached me,” and he “was tempted, and fell”. This time, he was offered a Fellowship at St John’s College, and for the next twenty years he dined at the college twice a week, but by his own admission was “never a very gregarious person.” Consequently, the trait that he had developed at LSE, of working in isolation, continued when he returned to Cambridge. He did little research in College (there were no individual staff rooms in the Squire Library), and worked at home, where now he has a collection of year book facsimiles in his basement.

Nevertheless, during his career Toby Milsom did make a significant communal contribution to legal history at a social and scholastic stage, when his interest in English legal history inevitably drew him into the Selden Society41. In 1964 he became its Literary Director, a position previously held by Plucknett who by then was not in very good health, but it was not a position Professor Milsom relished: “quite a tiresome job...if you’re producing a volume every year you’ve got to get people working on volumes and it’s never their top priority - it’s not going to do much for their CV. So you have to spend time hectoring them and then when they produce it, you have to read the damn thing, try and get rid of the grosser mistakes, and then see it through the press.”

In 1985 he was made President of the Society, but in retrospect, and I’m sure with tongue in cheek, ascribed ulterior motives to the Council “it was a dirty trick” they needed someone to shepherd the Society through its Centenary Year.

“Our Royal Patron was persuaded to do things and we had an enormous party and, because it was known that the Duke of Edinburgh was going to be there, hundreds of our American members crossed the Atlantic to be present at this party, and I’d never seen them, I had no idea who they were. And I said to the Equerry, look, I’m not going to be able to introduce these people. “Don’t you worry”, he said “just let him loose”, which I did and he was wonderful. He spent a happy evening talking to all kinds of people about all kinds of things that neither he nor they knew anything about. But he was really very good and there was a big dinner to which he came. .....I was concentrating on trying to introduce as many rich members as I could to the Duke.”

Professor Milsom’s tenure in the Faculty at Cambridge was served while it continued to occupy the quarters it had in his earlier days, namely in the same building as the Squire Law Library in the Old Schools, next to Senate House Passage. It had decamped to this site in 1937 and moved to its present location on the Sidgwick site only in 1995, by which time he had retired. Irrespective of the new technical facilities and greater space, he favoured the old quarters because “there was a little room – it could be used for various small seminars – but was generally regarded as otherwise useless, so we adopted it as our coffee room, and everybody met there at 11 in the morning. If you had to talk to a colleague, that was the time to catch him. So one did talk to them, and the Faculty knew each other”.

His recollections of colleagues are forthright, colourful and enlightening. Professor Bailey had by this time also retired from the Rouse Ball Chair (in 1968), but as a Fellow of St John’s was someone Toby Milsom still saw from time to time and described Bailey as slow, deliberate and with a very precise way of speaking.

One colleague for whom Professor Milsom had a high regard was Glanville Williams42, who, along with Professor Kurt Lipstein43, he described as “the true tenants of the Squire [Library]” (they each occupied one of the tiny offices that had nice view views over Caius). Williams had been a conscientious objector during the war, so that Trinity College would not have him as a Fellow - “Trinity High Table at that time was full of disapproving warriors”, so that the college “missed the most distinguished lawyer Cambridge has had for a long time.” (He became a Fellow of Jesus - 1955-97). Personally, Toby Milsom found him a “very nice man...the best approach to an absent-minded professor the Law Faculty ever had”, although being shy and having “chubby cheeks” and “looking a bit like a choirboy angel... must have been a disadvantage”. For Kurt Lipstein, he also had only positive memories: “he was a very nice man...always very helpful”.

Another colleague for whom he had a high regard was Professor Jack Hamson44 - “probably the cleverest man I ever met”. However, Toby found conversation with Hamson disconcerting because “everything that came his way he sort of chewed up in his mind”, while at the same time one was never sure “what or who he was looking at [as] he had serious cross eyes..”

During his time in his chair at Cambridge, Professor Milsom continued to publish on his expositions of the evolution of the common law, and in the process continued to suffer the slings and arrows, as well as accolades, of his legal histiographic audience, as he further continued the challenge to Maitlandian tenets he had begun in the mid-50s. But he did so with utmost deference - referring to himself as a “dwarf” on the giant’s shoulder, and a “lonely figure in some Bateman45 drawing, the man who thinks that Maitland was wrong46.”

Three more books appeared the years 1976-90, including a second edition of Historical Foundations (1981), a collection of his earlier papers (1985 Studies in the History of the Common Law), and the co-authored Sources of English Legal History (1986 with J. H. Baker), and during his retirement the work has continued from his home.

This period has entailed research on Maitland himself, and Professor Milsom has published several accounts that relate to Maitland’s remarkably short historiographic career (22 years), and reverently delves into the last years of the giant’s life which he devoted to a book of letters on his wife’s uncle-in-law, the writer Leslie Stephen47. This was a distraction of which Toby did not approve, seeing there were hints that Maitland could have modified some of his ideas with additional legal research in the time he had left, but Professor Milsom sympathised with the situation that confronted Maitland, and recognised the scale of the sacrifice he had made, given his state of health.

His last publication was A Natural History of the Common Law (2003) which arose from the Carpentier lectures that he gave at Columbia University in 1995, and it seems that the title and his introductory allusions to natural sciences are harking back to his earliest aspirations. Some of his reviewers warm to this theme, and both Ibbetson and Gardner use phrases such as “Darwinian evolution” and the “fossil record” in referring to Milsom’s conceptual development of and methods of exploring the common law.

After a career of intense, sometimes lonely research, this slim volume seems to epitomise Professor Milsom’s conclusions, and at the end, in what are probably destined to be some of the last words written by him, he set out his philosophy of understanding the development of the common law. “Things so obvious that they go without saying in their own day simply disappear.... [so that] the differences between the world [the historian] sees and the world he does not see cannot be checked off by noting changes in the detail. The devil is not in the detail but in the framework....[and that] is not something you can set out to look for; if you stumble upon it because distracted by incongruities when working within the framework, you must resign yourself to being a heretic48”. Professor Toby Milsom did just that for nigh on sixty years.

I interviewed Professor Milsom in his cottage tucked on the edge of town where Granchester Meadows passes into the riverside track along the Cam. It was a great privilege and pleasure to visit him, and, as listeners will discover, he remains a scholar with a delightfully dry, ironic wit, full of humour. His work has ensured that English legal history can never be spoken of in the future without mention of both Maitland and Milsom - the self-proclaimed dwarf has become a giant in his own right.

Lesley Dingle - Acquisition and Creation of Content

Daniel Bates - Visual Presentation, Technical Enhancement and Audio Editing

- 1 Professor David Ibbetson, 2004, Publication Review: “A Natural History of the Common Law”, Law Quarterly Review, 120; 696-700.

- 2 S. F. C. Milsom, 2001, Maitland, Cambridge Law Journal, 60 (2); 265-270.

- 3 1968, p. lxxi, Milsom’s introductory essay to the reissued 2nd Edition of Pollock & Maitland’s The History of English Law, CUP

- 4 See fn 2, p. 265.

- 5 p. xxiii, S. F. C. Milsom, 2003, A Natural History of the Common Law, Columbia University Press.

- 6 See fn 1, p. 696.

- 7 1838-1900, Professor of Philosophy at Cambridge, founder of Newnham College, 1871.

- 8 See fn 5, p. xiii.

- 9 See fn 2, p. 268.

- 10 Darrell Edward David (1919-40).

- 11 Captain Harry Lincoln Milsom.

- 12 Established in 1740. Currently called the Royal London.

- 13 2003, p. xiii, A Natural History of the Common Law, Columbia University Press.

- 14 Neurosurgeon. Inaugural Nuffield Professor of Surgery, Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, 1938.

- 15 William Warwick Buckland (1859-1946).

- 16 Destroyed in the 1936 great Crystal Palace fire.

- 17 Sir Percy Henry Winfield (1878-1953).

- 18 Henry Arthur Hollond (1888-1974), Rouse Ball Professor 1943-50.

- 19 Beatrice Mary Hollond, neé Hoare owned the grand country house called Great Ashfield House, near Bury St Edmunds. It was originally bought by his father in 1888 and built by the then Lord Chancellor, Edward Thurlow (1731-1806).

- 20 Patrick William Duff (1901-1991), Regius Professor of Civil Law 1945-68.

- 21 Lecturer in Law 1932-1959.

- 22 Emlyn Capel Stewart Wade (1895-1978), Downing Professor of the Laws of England 1945-62.

- 23 Sir Hersch Lauterpacht (1897-1960). Whewell Professor 1938-55, Judge at International Court of Justice 1954-60.

- 24 Sir Michael Kerr (1921-2002), Lord Justice of Appeal 1981-1989. Read law at Clare College 1939-40, and 1945-47. In As Far as I remember (2002) Hart Publishing

- 25 Sir Richard Stone (1913-1991), economist, Nobel Prize winner. Graduated from Gonville & Caius in 1936. In “The ET Interview: Sir Richard Stone”, Economic Theory, 2002, 7(1), 85-123.

- 26 President George Bush’s Secretary for Defense (2001-06).

- 27 Although he was not formally attached to the university, and spent only one week in digs in Christ’s College.

- 28 Professor Sir Robert Yewdall Jennings (1913-2004).

- 29 Now called Harkness Fellowships after the original founder, Anna Harkness (in 1918).

- 30 1907-94. Sometime Librarian at Yale Law School, and Professor of Legal History at Harvard.

- 31 1915-1991

- 32 University of Pennsylvania Law School

- 33 Professor Charles Homer Haskins (1870-1937). Harvard University 1912-31. Close advisor to US President Woodrow Wilson.

- 34 1889-1974. Born in Germany, emigrated to England in 1934.

- 35 Jurists Uprooted. German-speaking Émigré Lawyers in Twentieth-century England. Beatson J. & Zimmermann R. 2004, OUP, 850pp.

- 36 Mannheim was made a reader in criminology in the University of London in 1946 - the first readership in the subject established in the UK. See the LSE website: http://www.lse.ac.uk/collections/mannheim/hermannMannheim.htm

- 37 Theodore Frank Thomas Plucknett (1897-1965), Professor of Legal History, LSE (1931-63).

- 38 Novae Narrationes. 1963 Shanks, E. & Milsom SFC (edits) Selden Society, volume 80. Written during reign of Edward III (1327-77), it consists of three manuscripts constituting a precedent book containing selected models for students or practitioners.

- 39 John Blackstocke Butterworth (1918-2003) Later Lord Butterworth, inaugural Vice-Chancellor of Warwick University (1963-85).

- 40 1968, Pollock & Maitland: History of English Law, CUP; 1969, Historical Foundations of the Common Law, 1st Edit, Butterworths; 1976 The Legal Framework of English Feudalism (Maitland Memorial Lectures), CUP (based on lectures given in 1972).

- 41 Founded in 1887 by Frederic Maitland. http://www.selden-society.qmw.ac.uk/

- 42 Glanville Llewelyn Williams (1911-1997), Rouse Ball Professor (1968-78).

- 43 Kurt Lipstein (1909-2006). Professor of Comparative Law (1973-76).

- 44 Charles John Hamson (1905-1987), Professor of Comparative Law (1953-73).

- 45 H. M. Bateman (1887-1970) a cartoonist and artists famous for his “the man who....” pictures, featuring a buffoon perpetrating some social gaff.

- 46 Milsom, 1982. “F. W. Maitland, British Academy Lecture on a Master-Mind”, Proceedings of the British Academy, LXVI for 1980, 265-281, refer to p. 277 & 267.

- 47 1832-1904.

- 48 A Natural History of the Common Law, p. 107.

Twitter

Twitter

Instagram

Instagram Facebook

Facebook YouTube

YouTube